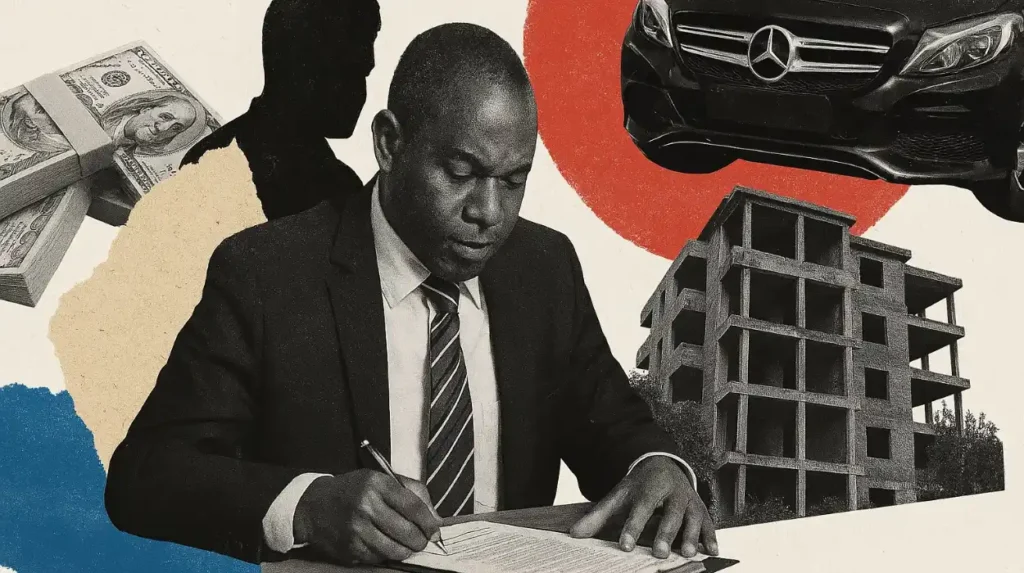

Dubai has become an epicenter for real estate money laundering, attracting wealthy individuals worldwide who use sophisticated methods, including anonymous shell companies, proxies, and cash transactions, to park illicit assets in luxury properties. This article exposes Ugandan nationals Alibhai, Hamid, Ezra, Mbuga, Serwamba, Bwambale, Nanteza, Lugudde, and Okumu—alleged to have covertly invested hundreds of millions USD in Dubai’s real estate market. Their activities highlight Dubai’s regulatory gaps enabling offshore wealth concealment and the broader impact on governance and financial integrity in Uganda and internationally.

Introduction: Dubai as a Hub for Illicit Wealth and Real Estate Laundering

Dubai’s high-end real estate market has evolved into a global playground for illicit wealth, offering a veil of secrecy that allows politically exposed persons (PEPs), criminals, and elites from various countries to launder money through property investments. Properties are acquired via complex layers involving shell companies registered in offshore jurisdictions and proxies, obscuring the true beneficial ownership. Cash payments and opaque financial channels further obscure transactions. Given Dubai’s limited regulatory transparency, these assets, often worth millions, are legitimized through rental incomes and resale, embedding illicit money into the formal economy without scrutiny.

Read AML Network’s exclusive report:

Report: Global Web of Corruption: 262 Individuals from 38 Countries Nailed in Dubai Real Estate Scandal

Mechanisms of Money Laundering in Dubai Real Estate

Laundering is typically structured in stages: placement, layering, and integration. Dubai’s real estate enables layering, where illicit funds are converted into high-value assets under anonymous corporate vehicles. Shell companies, often registered in tax havens, buy expensive villas and apartments. Proxies, including family members or business associates, are used to shield the real owners. Transactions mostly happen in cash or via complicated financial conduits, limiting tracking. After purchase, rental proceeds and resale generate apparent legitimate income, completing integration into the financial system. This model exploits Dubai’s lax regulatory environment, lack of enforceable public beneficial ownership registries, and tolerance for cash purchases.

Profiles of Ugandan Nationals Alleged in Dubai Real Estate Money Laundering

Alibhai

Alibhai is identified as a Ugandan businessman with longstanding political connections in Uganda’s elite circles. His wealth sources allegedly include politically linked construction and import-export businesses in Uganda. Investigative data suggest Alibhai controls multiple luxury apartments in Dubai’s Palm Jumeirah and Business Bay areas, purchased through an offshore company registered in the British Virgin Islands. These purchases were reportedly made mostly in cash with subsequent property management assigned to Dubai-based trust offices to obscure ultimate ownership. Alibhai’s Dubai properties serve as repositories to legitimize funds originating from Uganda’s infrastructure contracts.

Hamid

Hamid, a politically exposed figure with rumored ties to Ugandan government contracts, allegedly derives wealth from telecommunications and logistics enterprises in East Africa. Records indicate Hamid’s involvement in Dubai real estate acquisitions through a network of shell companies based in Seychelles and Cyprus. His portfolio includes high-end Jumeirah Beach Residences apartments and several villas in Dubai Hills Estate purchased under proxy names. These assets were acquired with largely unexplained cash deposits, a typical layering tactic, and rental yields reportedly reinvested through offshore trusts, complicating asset tracing.

Ezra

Ezra possesses a business profile linked to Uganda’s commodity trading and mining sectors. Allegations point to Ezra employing a series of anonymous companies to purchase properties in Dubai Marina and Downtown Dubai, worth upwards of $15 million. These holdings include luxury penthouses and retail spaces whose purchase prices were paid through non-transparent channels. Ezra is said to use nominee directors and proxies, including family members based outside the UAE, to mask his interest. The opaque ownership circumvents both Ugandan and Dubai regulatory scrutiny, facilitating offshore wealth concealment.

Mbuga

Mbuga’s background involves public service and involvement in real estate development within Uganda. Investigative leads link him to several real estate investments in Dubai Business Bay, specifically through a company registered in Panama. His wealth allegedly traces to public contracts and informal money flows, which he then layers via property purchases abroad. The properties were procured with cash and shell companies, with ownership further obscured by complex trustee arrangements in UAE free zones, a known facilitator of financial opacity.

Serwamba

Serwamba is a lesser-known but politically connected businessman in Uganda with interests in agriculture exports. Evidence suggests she bought multiple villas in Dubai Creek Harbour and luxury apartments in Meydan through offshore corporations in the Cayman Islands. These properties reportedly serve as investment fronts, with rental incomes and sales profits structured to provide a legalized cash flow. The transactions often lack clear paper trails, reflecting typical money laundering layering steps executed within Dubai’s lax enforcement framework.

Bwambale

Bwambale is linked to import-export businesses in Uganda and rumored political lobbying activities. Allegations surface of his real estate portfolio in Dubai comprising properties in Dubai Silicon Oasis and Emirates Hills, acquired through opaque offshore mechanisms based in Mauritius. Payment trails are purposely convoluted, designed to distance illicit origin funds from visible ownership. Bwambale uses management firms and nominee shareholders, adding layers of concealment between his personal identity and asset control.

Nanteza

Nanteza has a public profile tied to Uganda’s financial services sector, notably foreign exchange and remittance firms. She allegedly channels her wealth into Dubai real estate through a labyrinth of shell companies registered in Jersey and the UAE. Her portfolio reportedly includes luxury apartments at Jumeirah Lake Towers and mixed-use properties in Dubai Marina. Cash transaction dominance and proxy ownership structures make it challenging for regulators to connect her Dubai assets with questionable sourcing from Ugandan foreign exchange dealings.

Lugudde

Lugudde’s background is connected to the hospitality industry within Uganda, with investments in hotels and tourism infrastructure. She reportedly owns multiple villas in Dubai Hills Estate, obtained through offshore entities in Panama and BVI. These purchases frequently utilize third-party nominees and trust agreements to hide real beneficial ownership. The rentals and resales generate income that cleanly integrates previously illicit capital, exploiting Dubai’s deficient financial crime oversight.

Okumu

Okumu is involved in Ugandan transport logistics and is thought to use real estate as a money-laundering vehicle. His Dubai holdings span downtown apartments and properties in Al Barari, acquired through layered offshore companies with directors situated outside the UAE. He is alleged to pay cash for these assets, along with engaging private management companies to handle rentals, obscuring the link between him and the properties. Okumu’s strategy typifies the international pattern of illicit wealth parking in Dubai real estate.

Dubai’s Regulatory Environment and Its Role in Enabling Laundering

Dubai’s attractiveness for illicit financial flows stems from regulatory gaps including limited transparency on beneficial ownership, permissive cash transaction rules, and weak enforcement of anti-money laundering (AML) protocols within real estate. The Dubai Land Department and free zone authorities allow anonymous ownership through offshore companies and proxies with minimal due diligence. Such an environment has facilitated the embedding of billions in questionable funds in luxury property, often without investigations or asset freezes. This regulatory environment, coupled with Dubai’s global financial hub status, amplifies risks to international financial integrity.

Impact on Uganda and Global Financial Integrity

The activities of these Ugandan individuals in Dubai represent a significant drain on Uganda’s governance, as illicit wealth instead of being reinvested locally is siphoned offshore, weakening domestic institutions. Globally, such practices undermine efforts to combat corruption and financial crime, allowing illicit actors to profit without consequence. The concealment of wealth in Dubai’s opaque property market erodes transparency and fuels elite impunity, reinforcing cycles of corruption and poor governance that hinder social and economic development in source countries like Uganda.

Conclusion: Calls for Accountability, Transparency, and Reform

The cases of Alibhai, Hamid, Ezra, Mbuga, Serwamba, Bwambale, Nanteza, Lugudde, and Okumu illustrate the urgent need for strengthened international cooperation and regulatory reforms. Dubai must enhance AML enforcement, implement comprehensive beneficial ownership registries, and limit cash transactions to disrupt layering mechanisms. Uganda and the global community should prioritize asset tracing and recovery efforts, while promoting transparency in real estate markets. Only through sustained accountability and reform can the cycle of elite corruption and offshore wealth concealment be curtailed, restoring integrity to international financial systems and supporting governance in countries impacted by illicit financial flows.